By Dr. Richard Koch, Los Angeles Children’s Hospital

From the Fall 2003 issue of National PKU News

The year 1967 marked the beginning of a very important longitudinal study: The Collaborative Study of Children Treated for Phenylketonuria (PKUCS). With a beginning study group of 211 children from 15 clinics nationwide, the research continued for 16 years, until 1983, when the children were teens or pre-teens. A large number of papers in the scientific literature for PKU comes from the study of these children. But what happened to them after the study ended? Dr. Richard Koch of Los Angeles Children’s Hospital, principal investigator for the original study, decided to find out.

The original study, funded first by the Maternal and Child Health Division the Public Health Services and later by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), randomized the children in the study’s second phase. At age six, half of the group were assigned to continue the diet and half to stop the diet. This phase of the study intended to answer the question on the minds of many people at the time: is it safe to stop the diet in childhood? (The results of this study ultimately helped lead the way to a more universal policy of “diet for life”). When the study ended in 1983, most of the participants stopped treatment, despite efforts to keep them on the diet.

In 1998, NICHD scheduled a Consensus Development Conference to review all aspects of PKU treatment. As an adjunct to that review, Dr. Koch pushed for a follow-up study of the participants from the original collaborative study to evaluate their current medical, nutritional, psychological, and socioeconomic status. This research was subsequently funded by NICHD. Combined with the data gathered in childhood, this follow-up study offered a unique chance to look at the long-term effects of newborn screening, early treatment with diet, stopping the diet, and blood phe levels at various ages on a group of adults with PKU who had been followed since infancy.

Fourteen of the original fifteen clinics participated in the follow-up study of adults. Of the 125 original study subjects who had completed at least 10 years of follow-up, 70 were located. Only nine remained on the diet. The findings of this study appear in the Journal of Inherited Metabolic Diseases, 25: 333-346, 2002 (Koch, R., et. al., Phenylketonuria in Adulthood: A Collaborative Study).

Medical Findings

These findings are based on reports by the subjects and their clinic directors. The adults who had stopped the diet had many more problems than those who remained on the diet. The problems were more common among those who stopped the diet before 6 1/2 years of age. The most notable symptoms include a higher incidence of eczema among those off the diet (28% vs. 11% on-diet); hyperactivity (14% vs. none on-diet); lethargy and lack of energy (19% vs. none on- diet); recurrent headaches (31% vs. none on-diet); and neurological signs (24% vs. none on-diet) which were mainly increased or decreased muscle tone and deep tendon reflex changes. A variety of mental disorders including phobias, panic attacks, and depression afflicted 41% of those off-diet. Only 2 in the on-diet group reported transient depression not requiring psychiatric care. A large percent (54%) of the off-diet group had a variety of other problems not reported by the on-diet group.

Psychological Trends

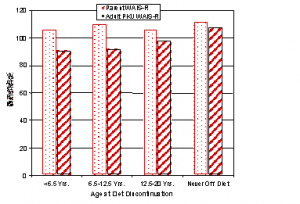

Intellectual development was measured by the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS-R). Figure 1 shows WAIS-R I.Q. scores based on age when diet stopped. Clearly, those who were never off the diet have done the best intellectually and also when compared to genetic expectations (their parent’s I.Q. scores). When evaluating these results, consider that the adults who remained on the diet had average blood phe levels at the time of the follow-up study that were not optimal (15 mg/dl or 926 µmmol/L, with several much higher ), and an average phe level of 10 mg/dl during childhood. Even so, the measured I.Q. scores of the on-diet group were within 3 points of their parent’s score. However, the off-diet adults had I.Q. scores significantly lower than their parents.

Intellectual development was measured by the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS-R). Figure 1 shows WAIS-R I.Q. scores based on age when diet stopped. Clearly, those who were never off the diet have done the best intellectually and also when compared to genetic expectations (their parent’s I.Q. scores). When evaluating these results, consider that the adults who remained on the diet had average blood phe levels at the time of the follow-up study that were not optimal (15 mg/dl or 926 µmmol/L, with several much higher ), and an average phe level of 10 mg/dl during childhood. Even so, the measured I.Q. scores of the on-diet group were within 3 points of their parent’s score. However, the off-diet adults had I.Q. scores significantly lower than their parents.

When adult scores were compared to those at age 12, significant increases were observed in I.Q. (both Verbal and Full Scale portions of the test) for those who never discontinued the diet. Statistical analyses showed that adult test scores were highly correlated with parental I.Q. and education, age at initiation of diet, age at treatment termination, and blood phe levels at various ages. That is, higher parent I.Q. scores and education, earlier treatment initiation, lower blood phe levels during treatment, and not stopping the diet all had beneficial effects on ultimate adult I.Q. scores.

Of 16 adults with classical PKU who resumed diet treatment, 9 were still taking the medical food and showed an increase in adult I.Q. compared to childhood. In contrast, 7 who did not manage to continue the diet experienced a drop in adult I.Q. compared to childhood. Interestingly, Individuals with classical PKU currently taking the medical food had significantly higher adult I.Q. scores than those on a regular diet, even when the blood phe levels were far from optimal.

Education and Occupation

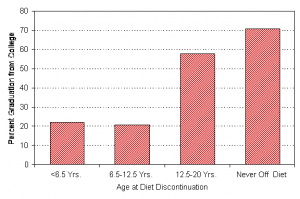

Of those who stopped the diet, only 32% graduated from college or had a postgraduate degree, while 78% of those who never discontinued the diet graduated from college or had a postgraduate degree (see Figure 2). Five of the off-diet group did not even graduate from high school. All of the adults who never stopped the diet had done at least some college work. Of those who never stopped the diet, 44% were in one of the two highest socioeconomic class categories, while only 20% of the adults who stopped the diet were in one of these two classes. None of the adults who had remained on the diet was in the lowest socioeconomic class, but 18% of those who stopped the diet were in this lowest class.

Of those who stopped the diet, only 32% graduated from college or had a postgraduate degree, while 78% of those who never discontinued the diet graduated from college or had a postgraduate degree (see Figure 2). Five of the off-diet group did not even graduate from high school. All of the adults who never stopped the diet had done at least some college work. Of those who never stopped the diet, 44% were in one of the two highest socioeconomic class categories, while only 20% of the adults who stopped the diet were in one of these two classes. None of the adults who had remained on the diet was in the lowest socioeconomic class, but 18% of those who stopped the diet were in this lowest class.

Other Findings

Twenty-two adults were selected for a pilot substudy of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). Ten adults were on the diet from infancy until at least age 10 (7 had never discontin-ued) and were currently taking the medical food as their primary source of protein. Twelve adults stopped the diet by age 10 years. A MRI scoring system of 1 to 3 was used. Zero indicates completely normal, where 3 indicates abnormalities of 3 regions of the brain. Seven adults in the on-diet group had a code 0 or 1 (70%) compared to only 6 in the off-diet group (56%). Patients with MRI code 0 or 1 had significantly lower brain phe concentrations than those with codes 2 or 3.

Conclusion

As previously indicated in the medical literature and confirmed by this study, discontinuing treatment has variable detrimental effects on the long-term medical and intellectual status of persons with classical PKU. We hope that new approaches to diet treatment will ultimately mean that more adults will continue diet “for life.